Rule-Based Language Technology: 11 1 This is Flammieâs draft, official version may differ. #1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Licence. Licence details: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Find the Publisher’s version from: https://dspace.ut.ee/handle/10062/89595

Abstract

In this article we discuss the ways finite-state technology has been used in natural language processing. This is not a complete overview, but tries to introduce some of the more popular use cases and software. The biggest use case I go through is finite-state morphology and its use cases. I also discuss the way probabilities were brought into classical non-weighted finite-state systems.

Key Words: Finite-State methods, NLP, Morphology, Morphological analysis, Morphological dictionary, spell-checking, NER (Named Entity Recognition)

1 Introduction

Finite-state technology is a central part of the rule-based natural language processing. Finite-state automata (FSA), or finite-state-machines more generally, have been studied in mathematics and computer science through the 1900s (Hopcroft et al., 2001). In computer science, finite-state machines have been integral to the invention and development of compilers (Aho et al., 2007). Regular expressions (RE) are closely related to finite-state machines (FSM) so that REs can be mechanically converted into FSMs. REs are often used for searching from complex patterns from texts as in Unix grep commands. Many linguistic concepts such as text corpora, word lists, lists of morphs or morphemes, or even phonological rules can be represented as REs or FSMs. These kinds of FSMs are used in practice for morphological analyzers. We often call these morphological analyzers also language models. This is a term used in the statistical and neural language processing for similar components, that can process strings of natural language and give it readings, for example probabilities. In modern finite-state technology the same is true: we use a finitestate analyzer to give a string analysis and a weight estimate. The finite-state theory has also been studied as a part of formal language theory and linguistics, as a theoretical model, for example, in Chomsky’s hierarchy of languages, in which the regular languages are understood to correspond to natural language morphology. In natural language processing the finite-state machines have been used since the 1980s.

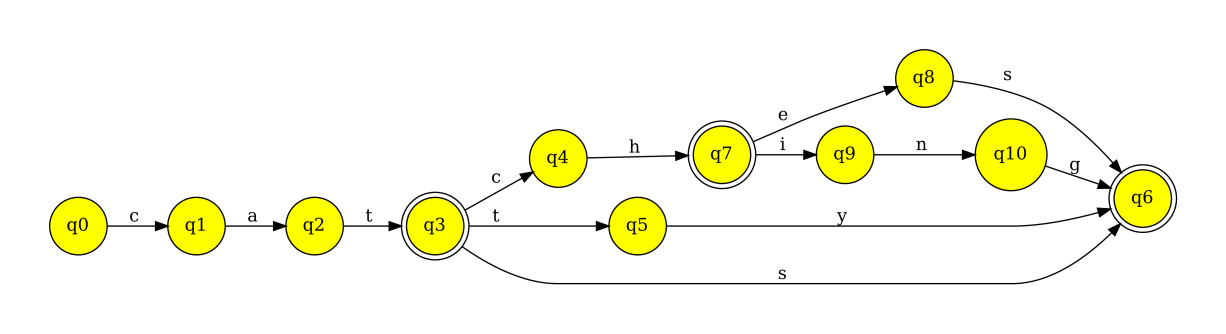

The attraction of finite-state machines in processing natural languages lies in its efficiency. The processing speed of texts when using finite-state machines is superior to naïve character string manipulation methods (Aho and Corasick, 1975). Finite-state machines are also efficient in encoding linguistically important concepts such as word lists and even morphological analyzers. As an example, in Figure 1 we show a finite-state automaton that contains a morphologically aware dictionary of English word-forms ‘cat’, ‘cats’, ‘catty’, ‘catch’, ‘catches’ and ‘catching’. If you set them in a list or a database you can imagine the prefix cat is repeated for each word-form, whereas in the automaton form it can be shared. On the other hand, the usage of finite-state automata is also intuitively fast; to find out whether ‘car’ is encoded by the automaton one only follows the ‘c’ and ‘a’ from the beginning of the automaton to run into dead-end, and this is systematically the case for usage of finite-state machines of any complexity. Furthermore, the finite-state automata allow loops in the graph structure, enabling a linguistic concept of compounding, so if English were a normal compounding language, you could have a machine recognizing also forms like ‘*catcatching’ or ‘*catcatcats’ with simple addition of one cycle in the network, specifically from q3 to q0.

For mathematics and computation, the finite-state machines are interesting since they form an algebra that makes operating on the models easy: Finite state automata can be combined by operations such as ‘and,’ and ‘or,’ (i.e., conjunction and disjunction or union respectively), concatenation, reversion, repetition etc. Many of these operations also make sense when building representations of natural language features: affixation can be modelled by concatenation, compounding can be modelled by repetition, and allomorphy can be modelled by operation ‘or’ intuitively. This makes the finite-state approach of language modelling easy to work on.

There are several tools that implement finite-state algebra for natural language processing purposes: HFST22 2 https://hfst.github.io , (Lindén et al., 2009) foma33 3 https://github.com/mhulden/foma/ , OpenFst44 4 https://openfst.org , Kleene (Beesley 2012) are freely available and open source and have been in active use in recent times. Also, python-based systems such as pynini have been used. (Gorman, 2016) There are of course, these are the ones I have worked on, and I have found them useful. Notably, e.g., in speech technology, a toolkit called Kaldi is popularly used. Still, their representation and usage are vastly different from the others I refer to here, and outside the scope of this introduction.

2 Morphology

If you consider natural language processing technology in the form of tools built from building blocks, morphology is usually one of the most basic building blocks. The most basic form of morphological dictionary is just a list or a database of word forms. It will be sufficient for most languages that have a limited morphology. Even compiling such a list into a finite state automaton will make it efficient.

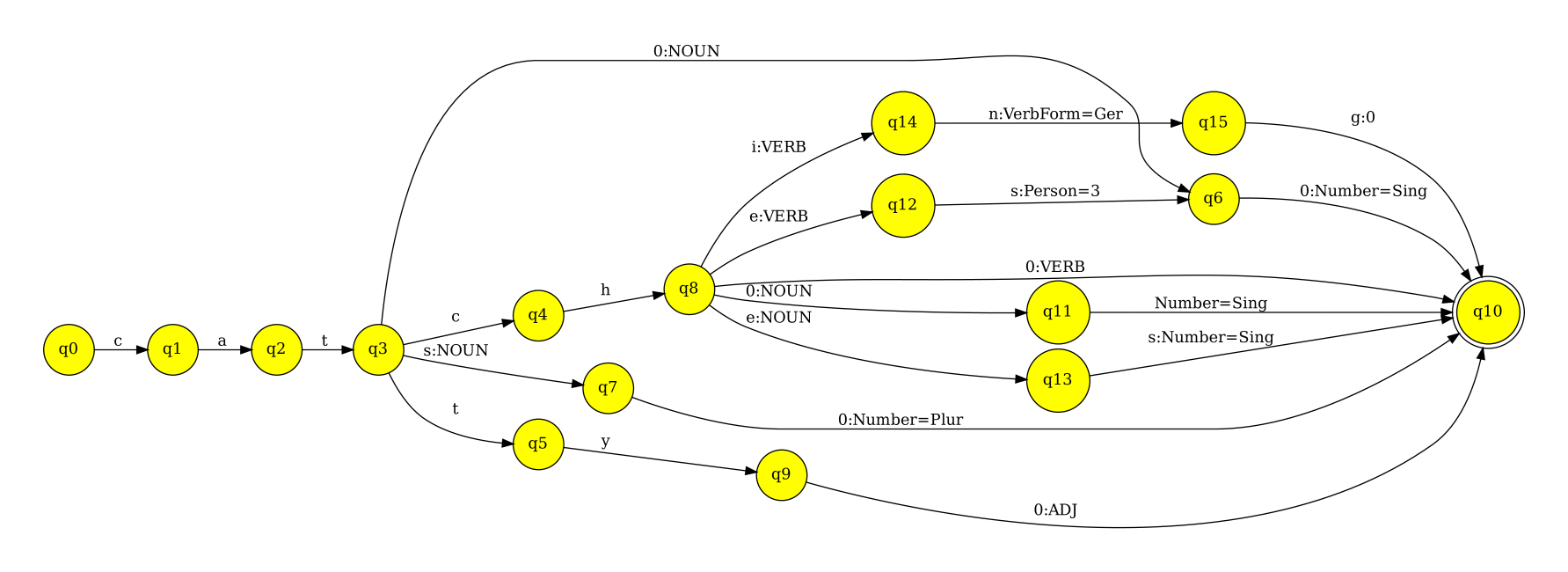

Most Natural Language Processing (NLP) applications, apart from spell-checking,

need the analysis of the word-forms. The most typical form of analysis used in

the rulebased NLP for word-forms is lemma or citation form plus a few

morpho-syntactic analyses. To return to the simplified example in Figure 1, we

have a finite-state analyzer of same word-forms in Figure 2. It is noteworthy

that the structure of this network is already different, even though it encodes

the same set of the words, we have made space for the analyses and the ambiguity

between English words such as ‘a catch’ (noun) and ‘to catch’ (verb). One could

argue that ambiguity of these English words is even richer, however, the limited

set of readings I show here is enough to illustrate my point. You can find an

example implementation of this morphological analyzer in Finite State Morphology

(Beesley and Karttunen, 2003) style lexicons in Figure 2. In practice in this

paradigm, you use ‘lexicons’ to contain sets of morphs that are combined in a

left-to-right order, e.g., Root-VerbVerbInflection-#, where Root is the

special case of starting lexicon and # is the special case of ending

lexicon.

Multichar_Symols NOUN ADJ VERB Number=Sing Number=Plur LEXICON Root 0:0 Verbs ; 0:0 Nouns ; 0:0 Adjectives ; LEXICON Verbs catch VerbInflection ; LEXICON Nouns cat NounInflection ; catch NounInflection ; LEXICON Adjectives catty # ; LEXICON VerbInflection Tense=Present:es # ; LEXICON NounInflection Number=Sing:0 # ; Number=Plur:s # ;

Another noteworthy theoretical difference between the finite-state machines of Figures 1 and 3 is that the first is a so-called single tape automaton, whereas the second is a two-tape automaton. A two-tape automaton is commonly also called a finite-state transducer (FST). The finite-state transducers are so named because they in practice encode a relation between two strings, e.g., an abstract representation and a word form found in a text. In many applications, we only use analysis. Still, for example for applications such as machine translation, dialogue systems, or just natural language generation, the other direction is used as well. If you need a plural of the noun ‘cat’ you can generate that from these abstract formulations.

A note must be made also to the concept of the representation of abstract features in the automaton, i.e., analysis tags and lemmas. In Figure 3 we have used lemmas that are commonly found in dictionaries, we have used a part-of-speech tag from the Universal part-of-speech inventory (Petrov et al. 2011), and we have used the morphosyntactic features from the Universal dependencies’ standards (de Marneffe et al. 2021). Following a systematic annotation between the languages is particularly important for the working of applications such as machine translation, for generalization and re-use of higher-level applications altogether. Because historically, computer linguists have selected these representations in ad hoc strings depending on the applications they are encoding or the linguistic framework they are working with, but history has shown that badly defined tag sets and annotation schemes that are hard to get to interoperate reduce the usability of otherwise well-built morphological dictionary

Obviously, a simple word-form list is insufficient for any language that can be considered morphologically rich. For example, for Finnish, even creating a list of all forms of a single noun, will result in some thousands of word forms, instead of two forms in English. Given average dictionaries used for high-coverage analyzers are from 100,000 words upwards, you would be generating at least several gigabytes of data. Even with modern systems having enough memory to hold and process such datasets easily, this is very suboptimal and wasteful. The solution to this was finite-state modelling of morphology: morphotactics and phonology (Koskenniemi, 1983, Beesley and Karttunen, 2003).

2.1 Morphotactics and morphophonology

The idea in morphotactics is still quite similar as a starting point: we have lists of morphs instead of full word-forms. The morphs are arranged in combinations as one would do in grammar: start from noun prefixes, then go to noun roots or stems, then noun suffixes, and if there is compounding, loop back to e.g., noun roots. For example: we can form Finnish word from morphs ‘epäjärjestelmällisyydellänsäkään’ (by their unorderliness too) by taking prefix ‘epä’ (un), root ‘järjestelmällisyyde’ (orderliness), and suffixes ‘llä’ (on), ‘nsä’ (their), ’kään’ (too). Listing the set of morphs and their combinatorial rules, we only need to list all dictionary words once and each morph once.

For many languages, simply chaining morphs together is insufficient, either the morphology is more synthetic and less agglutinative, or there are many complex morphophonological processes causing stem and affix variations. One of the most common solutions to this is two-level morphology, (Koskenniemi, 1983; 2019) where instead of chaining together morphs, you use morphemes, and write rules concerning the sound changes in different word forms. To take the example of ‘epäjärjestelmällisyydellänsäkään’ again, we can note that the lemma form and singular nominative of the root is ‘järejstelmällisyys,’ i.e., there is a s, de, te, t, ks variation in the stem. On the other hand, we also know that Finnish has vowel harmony and thus the suffixes ‘llä,’ ‘nsä,’ ‘kään’ have back vowel harmony variants: ‘lla,’ ‘nsa’ and ‘kaan.’ From experience and linguistic knowledge, we can implement the morphology with generalized morphemes ‘järjestelmällisyy0kstde0’ and ‘llaä’, ‘nsaä’, ‘kaäaän’ makes morphotactics simpler and more elegant at the price of more complicated rules for morphophonology. Here we have presented morphophonemes with curly-bracketed expressions instead of e.g., capital letters for clarity and because it causes fewer problems in long-term maintainability if you use it as an implementation.

When you deal with morphologically complex languages, there are also several other issues to deal with, such as reduplication, infixation, nonconcatenative or non-continuous morphology. There are several approaches to all of these, ranging from just listing all combinations to computing those lists mechanically either by separate scripts or by using equivalent methods in e.g., the XFST formalism. Furthermore, this scripting language is often used in later stages of the writing full-fledged finite state morphological dictionaries, often to patch out some corner cases and exceptional orthography rules that would be hard to implement throughout the dictionaries at that stage of the development. For example, if compounding language has special rules of collapsing triple characters in compound boundaries, it is possible to write a fixup rule in style of x -¿ x x in scripting language such as hfst-xfst in finite-state morphology. While this kind of scripting approach can be often tempting to implement features of morphology, it typically does decrease the maintainability of the overall system; thus, they should be used with care.

2.2 Weighted Finite-State Technology

Finite-state morphology traditionally produces all linguistically plausible analyses word forms, but this ambiguity is not often what end-users want. Constraint Grammar (Karlsson, 1990) and similar systems were designed to reduce this ambiguity, it turns out that for large classes for ambiguity resolution, some knowledge of the frequency of the word in general or in a specific context helps in choosing the correct sense. Such information is useful evidence towards high-quality disambiguation. While it is possible to encode the likelihoods of words or morphosyntactic features by hand, e.g., ‘dog’ is more common than ‘common clothes moth’55 5 a real-world disambiguation problem from Finnish, i.e., in word form ‘koirasta’ (of dog or moth rasta) and genitive accusative is more common than the instrumental case, if one has the luxury of large, high-quality corpora, one can also estimate the probabilities using such most frequently used words as quoted from Wiktionary66 6 https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Wiktionary:Frequency_lists/TV/2006/1-1000. The tools to make use of such frequencies are so-called weighted finite-state automata (WFSA), an extension to the classical finite-state system that adds “weights” to the accepted strings. Weights can be thought of as probabilities. For computational reasons, the so called “tropical weights”77 7 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tropical_semiring are used in the systems described in this chapter. Tropical weights work such that bigger is worse, and they can be combined by addition (instead of multiplication with probabilities), this makes calculations more maintainable. (Multiplication of many small probabilities will cause problems with floating point arithmetic.) Mathematically, one can map probabilities to weights by formulas e.g., , where W is weight, P is probability and log is a logarithm. In practice, slightly more advanced formulations are used to estimate the probabilities to also consider word forms that are not seen in the corpus, for further information on this the weights can be assigned manually in order to induce the preferred analyses to be.

you 1222421 I 1052546 to 823661 the 770161 a 563578 and 480214 that 413389 it 388320 of 332038 me 312326 ...

3 Finite-State Applications

Finite-state technology has been used for many NLP applications either directly using finite-state software libraries or indirectly by using the analyses of the finite-state morphological dictionaries. One of the most popular applications of rule-based natural language processing and finite-state technologies is spell-checking and correction. The fact that spell-checking and correction needs to be strict about a specific norm of a language makes it ideal use-case for rule-based language processing, since it really is about using rules of the language and explaining them to the end user, a concept that is the weakest point of corpus-driven technologies like statistical and neural modelling of the language. Other popular applications of finite-state technology within natural language processing include named-entity recognition, Finite-state technology-based machine-translation is also one of the more popular rule-based machine translation applications, this is further detailed in the Apertium chapter of this book.

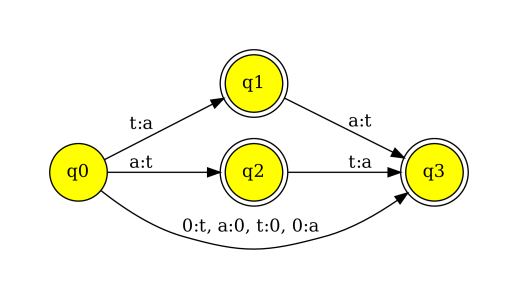

Finite-state spell-checking and correction builds on the morphological dictionaries of finite state morphology. The words identified by the analyzer are considered correctly spelled; those out of vocabulary are then considered misspelled. For example, ‘cat’ would be acceptable word in English whereas ‘cta’ would not be and would be highlighted by a spell-checker with a red squiggly underline. To correct the misspelt word-form a finite state model can be applied, that tries to undo the spelling errors, for example, in this case to reverse the order of characters t and a. The most common spelling correction used since the early spell-checkers and correctors is so-called Levenshtein or Damerau edit distance algorithm, which allows removal, addition, change or swap of two characters. There is a simple finite-state formulation of this that works efficiently, shown in figure 5 for characters a and t. The algorithm can be further optimized by using specific weights for corrections, for example to consider the keyboard layout. Since finite-state models are easily combinable by finite-state calculus one can also easily add various arbitrary and specific correction mechanisms and freely mix and match them. For example, if writers make mistakes with specific words, suffixes, or letters, we can add and reweight them as specific rewrites to this finite-state model

Named entity recognition is a common NLP application for morphological analyzers. It extends the analysis by identifying certain multi-word patterns. For example, first name and surname form a named entity referring to a person. In HFST (Helsinki Finite State Tools) tools, there is a scripting language for this purpose called hfst-pmatch. See figure 6 for example of how this scripting language is used (example simplified from Kokkinakis et al., (2014)). What these rules describe is that we aim to find words spelled in capital letters and tag them as people, if two such words appear next to each other; in practice rules for named entity recognition are of course more complicated, but the main point is that such applications can be built on finite-state framework readily.

define NoSpTag [? - [Whitespace|"<"|">"]]; define CapWord2 UppercaseAlpha NoSpTag+; define Person CapWord2 [" " CapWord2]* EndTag(Person) ; define TOP Person;

4 Further Reading

There have been several books written specifically about finite-state methods in natural language processing. We did not go deep into all technical and mathematical details within this book, the interested reader is suggested to read Gorman and Sproat (2021). There are also several valuable resources on the use of finite-state technology in course books that cover natural language processing in general to set finite-state language processing into a larger context (Manning and Schütze, 1999, Jurafsky and Martin, 2000).

For historical reference of the Finite-State Morphology as paradigm, I recommend reading the following books in order; this order conveys the idea on how it was developed even if it is not order of appearance:

-

•

Koskenniemi, (1983; 2019b): Two-Level Morphology

-

•

Beesley and Karttunen (2003): Finite-State Morphology

-

•

Karlsson et al. (1995): Constraint Grammar

While Karlsson et al., (1995) is not finite-state technology, it is systematically only used in conjunction of finite-state morphological dictionaries, and for many upstream applications it is the missing piece. The robustness of handling fully ambiguous linguistic analysis is often difficult to implement by the application programmers and many applications do expect that there is one correct analysis per word. In statistical paradigm this is achieved by operating on 1-best analyses as a starting point, but this has not been a frequent practice in rule-based natural language processing. Some new developments were documented later by Roche and Schabes (1997). For specific innovations within the finite-state technology, there are several research groups and industry representatives who have worked on usage of the finite-state methods in natural language processing, not to mention a conference series: FSMNLP (Finite-State Methods in Natural Language Processing). I list here only a few influential works but there are many more. For the concept of weighted finite-state automata, that all modern finite- state systems use and that brings finite-state, rule-based methodology closer together with statistics-based corpus-driven language processing, the best source is OpenFst’s publication list. Specifically noteworthy as a general introduction is Mohri, (1997, 2004). For the finite-state spell-checking and correction, I have written a summary article (Pirinen, 2008), which gives a good overview summarizing my thesis on the topic that contains pointers on the technology. On grammar-checking and correction (Wiechetek et al., 2019) describes usage of finite-state morphology and constraint grammars for the task. The usage of finite-state automata in Apertium is described in the Apertium chapter of this book, but for underlying techniques for example (Carrasco and Forcada, 2002). An example of potential approaches in use of finite-state morphological dictionaries in modern treebanking are described in Tyers and Sheyanova, (2012).

5 Conclusion

In this article I introduced some background of finite-state technology in natural language processing. I showed a few examples of the total toolchains of finite-state applications such as spell-checking and correction.