Language technology for the minority Finnic languages

Authors: Flammie A Pirinen

Divvun — UiT Norgga

árktala\v{s universitehta

Tromsø, Norway

first.last@uit.no

and

Trond Trosterud

Giellatekno — UiT Norgga

árktala\v{s} universitehta

Tromsø, Norway

first.last@uit.no

and

Jack Rueter

Helsingin Yliopisto

Helsinki, Finland

Affiliation / Address line 3

first.last@helsinki.fi

}

Abstract: This article gives an overview of the state of the art in language technology tools for Balto-Finnic minority languages, i.e., Balto-Finnic languages other than Estonian and Finnish. For simplicity, we will use the term Finnic in this article when referring to all members of this language branch except the Estonian and Finnish literary languages. All in all, there are nine standardised languages represented in existing language technology infrastructures with keyboards, grammatical language models, proofing tools, annotated corpora and (for one of the langauges) extensive ICALL programs. This article presents these tools and resources, discusses the relation between language models and proofing tool quality, as well as the (potential) impact of these tools on the respective language communities. The article rounds off with a discussion on prospects for future development.

Introduction

In contemporary Uralic language technology, the majority languages of the countries such as Finnish, Estonian and Hungarian are well researched and documented, whereas minority languages lack some of the resources. For example, in terms of mapping the status of language technology of European languages, there exist two series of white-papers from the central European research infrastructures, one by Springer (cites: koskenniemi2012finnish,liin2012estonian,simon2012hungarian) and another by ELE (cites: muischnek2022report,linden2022report,jelencsik-matyus2022report). For minority languages in the Nordic countries, there are also two such reports ((cites: moshagen2022report) and (cites: steingrimsson2024language)). Two Finnic languages were covered by the two last reports (Kven and Meänkieli), but, to our knowledge, no such overviews exist for the Finnic minority languages as a whole. One of our aims is to fill that gap.

Much of the Finnic language technology has been done within the GiellaLT infrastructure (footnote: https://giellalt.github.io, see also (cites: pirinen-etal-2023-giellalt,moshagen2023giellalt)), where the present authors all have been active, but both the Apertium (footnote: https://apertium.org, (cites: khanna2021recent)) and Neurotõlge (footnote: https://neurotolge.ee, (cites: yankovskaya2023machine)) machine translation systems have been applied to Finnic languages as well. In this paper, we give an overview of current and ongoing work in the field of Finnic language technology.

Background

This section gives a brief presentation of the languages and thereafter the technological foundation for the language technology used with them.

Languages

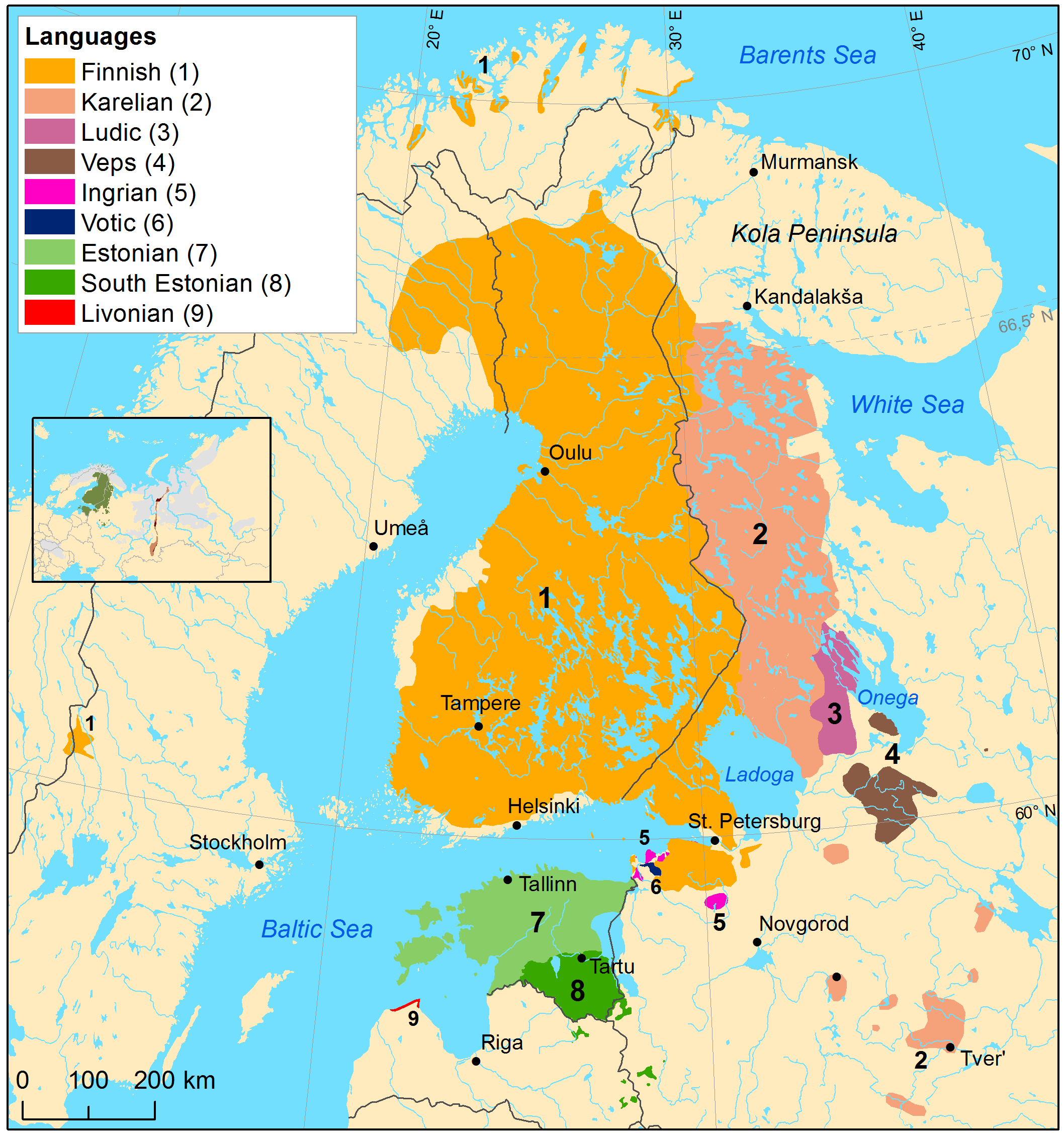

Figure:

(Caption: The Finnic Languages (cites: rantanen2022best))

(¶ map)

(Caption: The Finnic Languages (cites: rantanen2022best))

(¶ map)

The Finnic language area is shown on the map in Figure (see: map). The map is ordered according to linguistic criteria and does not quite correspond to the written Finnic languages. Subsumed under (1) in the map are also Meänkieli and Kven (marked as “Finnish”) on the Swedish and Norwegian side of the border in Northern Fennoscandinavia, respectively. Within the South Estonian area (8) there is only one written standard, whereas the Karelian area (2) covers North Karelian Proper (krl) and Livvi (see (see: howmany) below for a discussion). Outside the present presentation fall the majority languages (Estonian and Finnish). This leaves us with a linguistic map quite close to the 11 Finnish language codes, shown in Table (see: lgs).

Table:[ht]

| Language | ISO | Glottolog | Finnish | |

| —- | —- | —- | —- | —- |

| Meänkieli | fit | torn1244 | meänkieli | |

| Kven | fkv | kven1236 | kveeni | |

| Karelian | krl | kare1335 | karjala | |

| Livvi | olo | livv1243 | livvi | |

| Ludic | lud | ludi1246 | lyydi | |

| Veps | vep | veps1250 | vepsä | |

| Ingrian | izh | ingr1248 | inkeroinen | |

| Votic | vot | voti1245 | vatja | |

| Võro | vro | sout2679 | vöro | |

| Livonian | liv | livv1244 | liivi |

(Caption: Names and codes for the Finnic minority languages) (¶ lgs)

All the Finnic minority languages are written in the Latin script, using orthographic principles much in line with the ones used for Finnish. Typologically, the language branch is quite homogenous, the languages are mainly agglutinative with rich case systems for the nominals and tense-mode systems for the verbs. The size of the case systems ranges from 8 (Livonian, (cites: Viitso-et-al-2012-livokiel), (cites: laakso2022livonian)) to 18 (Veps, (cites: grunthal2022veps)), and most of the languages use possessive suffixes for all nouns. Most of the languages have consonant gradation and vowel harmony, whereas Livonian and Veps have neither.

All the Finnic languages are presented in two recent handbooks on Uralic languages, (cites: bakro-nagy2022uralic) (footnote: See especially the chapters on Ingrian (cites: markus2022ingrian), Karelian (cites: sarhimaa2022karelian), Livonian (cites: laakso2022livonian), Seto (cites: pajusalo2022seto), Veps (cites: grunthal2022veps), Votic (cites: markus2022votic).) and (cites: abondolo2023uralic) (footnote: Relevant chapters are (cites: grunthal2023finnic) on Finnic and (cites: pladoetal2022voro) on Võro.). Kven is presented in (cites: soderholm2017kvensk) and Meänkieli in (cites: pohjanen2022meankieli).

Technologies

The main technologies used for language modelling in the GiellaLT infrastructure are Finite State Morphology (cites: beesley2003finite[FSM]), Constraint Grammar (cites: karlsson1990constraint[CG]), and Two-Level Morphology (cites: koskenniemi1983twolevel[TWOL]). This means that morphology and syntax is implemented based on (hand-written) dictionaries of lemma-stem pairs and on rules governing morphology, morphophonology and syntax. These dictionaries and rules are then compiled into finite-state automata for efficient processing. Contextually determined disambiguation and higher level syntax rules are written in constraint grammar and processed programmatically. The grammatical models are compiled with Helsinki Finite-State Technology (HFST) (cites: linden2009hfst) and the constraint grammars with VISL CG 3 (cites: bick2015cg), both free and open source products. HFST is based on weighted finite-state automata and can contain statistical information about words and word-forms. Throughout this article, we use the term language model broadly for any system that can analyse or validate word-forms and may or may not have statistical information. The grammatical model is used to point to the rule-based model consisting of the traditional FSM, CG and TWOL.

The source code for the grammatical models is stored on Github as open source (footnote: <htts://github.com/giellalt/>, see https://github.com/divvungiellatekno for a full overview). The applications that can be developed with the language models include spell-checking and correction, grammatical error correction, computer-assisted language learning and speech technology applications.

The GiellaLT infrastructure also holds corpora. They are used both for development and testing of the language models and are presented as annotated corpora, accessible via dictionaries or for corpus linguistics (footnote: https://gtweb.uit.no/korp). The tools are also used in collaborative infrastructures, such as the Language Bank of Finland Korp server (cites: rueter2024testing). For minority Uralic languages, the availability of texts in general is limited, and certain genres might be totally absent. The variance in “quality” in relation to standards is more extensive than what is available for majority languages that have long established writing systems.

The universal dependencies project (cites: ud214) contains several Finnic language datasets: Karelian and Livvi have been built based on GiellaLT analysers and manual annotation (cites: pirinen2019building).

The grammatical models generate paradigms and the corpora present usage expamples for digital dictionaries for most of the Finnic languages (footnote: The dictionaries are available at https://sanat.oahpa.no (Kven, Livvi, Meänkieli, Veps) and https://sonad.oahpa.no (Ingrian, Liv, Võro and Votic), respectively.). The dictionaries are very useful for language communities and language learners (footnote: See e.g. (cites: raisanen2024kvensk) for an analysis of the role of the Kven dictionary in revitalisation.).

The underlying technology for rule-based machine translation of the minority Uralic languages is traditionally based on the Apertium tools (cites: khanna2021recent). What this means in practice is that we can make use of the above-mentioned Finite State Morphology for language modelling, and add to that bilingual (translation) dictionaries, and grammatical rules concerning about structural re-ordering of words and phrases to implement the machine translation.

In recent years we have also started to develop speech technologies, while this is not yet production quality for the languages mentioned in this article, we are hopeful that the successes shown, for example, for Saami languages by (cites: hiovain2023developing) will be transferable to Finnic minority languages as well.

In recent years within natural language processing, the use of large language models and neural networks has become more popular and widely replaced rule-based technologies. While this works for larger languages with plenty of available language data covering all textual genres and containing largely grammatically correct and correctly spelled language, this is more challenging and produces still less optimal results for minority Uralic languages. For this reason, the first step for us is usually to get rule-based tools that promote language revitalisation and writing normative language, that is, creating more language data that these large language models need as a prerequisite.

There exists some work done in the Uralic neural network model space, especially within machine translation, (cites: yankovskaya2023machine) have released systems for minority Uralic languages, see Table (see: neural) below for a discussion.

Grammar models and standardisation

When making grammatical language models, one always has to make choices: Some grammatical forms are included in the model, others are not. When the models are turned into proofing tools and similar programs, the normative aspects become central linguistic questions. On the other hand, when models are used in search engines or speech technology, a completely different set of questions over inclusion of words and word-forms arises.

How many standard languages?(¶ howmany)

The international standard ISO 639-3, Codes for the representation of names of languages, lists 9 Finnic languages (c.f Table (see: lgs)), in addition to standard Finnish and Estonian. This has profound consequences in a language technology setting, as the ISO codes are used by the operating systems as identification of languages for proofing tools, for example, in text editors, localisation of user interfaces, speech technology, etc. A language without an ISO 693-9 code is thus invisible to the computer. Any language community in search of literacy thus needs an ISO language code.

According to (cites: laakso2022graphization[93f]), there are literary languages for Veps, Livonian, Meänkieli and Kven as well as a common literary language for Võro and Seto. Laakso and Skribnik do not mention written languages for Ingrian, Ludic or Votic but for Karelian they report that there exist “at least three different written forms for the diverse dialects of Karelian”.

As seen in Table (see: lgs), there is no separate tag for Seto, and vro is assigned to Võro. Glottolog the ISO standard, aligns the ISO code vro with Glottolog code sout2679 for South Estonian, this node then contains 13 subnodes, two of them are seto1244 for Seto (itself with 3 subnodes) and voro1243 for Võro. If Laakso and Skribnik are correct, the ISO code vro may be used for identifying the Seto-Võro written language.

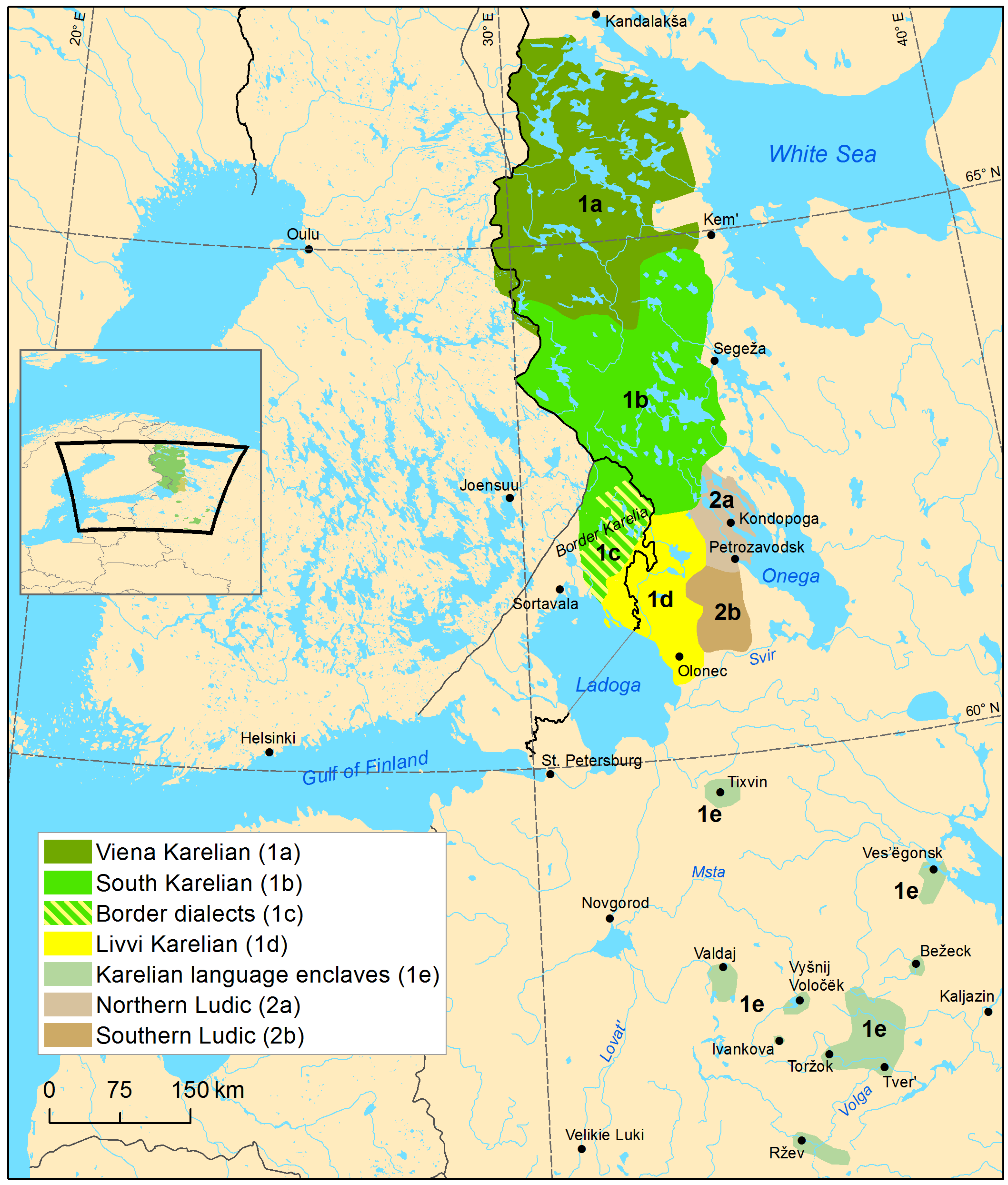

The most problematic part is Karelian. ISO offers the code quadruplet krl, olo, lud, vep, for Karelian, Livvi, Ludic and Veps, respectively. The traditional distribution is shown in Figure (see: map:karelian).

Figure:

(Caption: Karelian and Ludic around 1900 (cites: rantanen2022best))

(¶ map:karelian)

(Caption: Karelian and Ludic around 1900 (cites: rantanen2022best))

(¶ map:karelian)

According to the corpus data presented in (cites: boyko2022open), Chapter 2.1, the ISO codes are actually quite appropriate for the situation at hand. They present 4 corpora, for the languages “Veps, Livvi, Ludian and Karelian proper”, i.e., an exact match with the existing language codes. As long as no standard is claimed for South Karelian ((1b) in Figure (see: map:karelian), the ISO code inventory provides a good tool for making proofing tools for the Finnic languages of Russia.

Meänkieli and Kven: Many norms in one

Kven and Meänkieli pose a different type of challenge. Here, the ISO codes, are

unambiguous, the problem is rather that some speakers would like to distinguish

between three standardised varieties for both Kven

(c.f. (cites: soderholm2017kvensk)).

and perhaps also for Meänkieli (incidentally, Glottolog offers 3 codes for

Meänkieli dialects but none for Kven). Obtaining different ISO language codes

for these would probably be problematic, but so is the situation of missing

support for the (emerging) varieties. So far, the problem has been solved in

different ways for these two langauges. For Meänkieli, the analyser includes all

variant forms on an equal footing, thus allowing for (even inconsistent)

variation in writing. For Kven, there is one grammatical model for all three

dialects. We here show a snippet of code for nouns with short vowel stems for

two of the Kven dialects, Porsanki and Varanki. Both share the same genitive

suffix, but the partitive suffix is set to the archiphoneme \^{A} for

the Varanki dialect and \^{V} for the Porsanki dialect. Then TWOL

rules (footnote: for detailed technical description on TWOL refer

to (cites: koskenniemi1983twolevel)) will spell out the actual forms of \^{A}

(as a when the stem contains aou or ä elsewhere) and

\^{V} (as a copy of the preceding vowel). During compilation, we build

one transducer for each dialect, by removing the strings containing the other

dialect tags for each dialect, and thereafter the dialect tag of the dialect

desired (but not the string containing it). The genitive case is common to both

dialects (as is most of the morphology), it receives no dialect tags and is kept

throughout compilation.

So far, only the Porsanki dialect has been distributed to language users. Having all three co-existing in the same computer would not be possible, as they must be referred to by the same ISO code, so if the need should arise we would have to ask the users to install only one of them.

Data-driven and/or rule-based language technology

A hot topic in NLP of 2020’s is, what all can be done with large language models and chatbots. Our approach to NLP is based on traditional rule-based systems, with expert curated dictionaries and hand-written rules. For languages we talk about in this article, it can be easy to point out that for data-driven approaches we simply do not have enough data (c.f. Sable (see: subsec:corpora) for some statistics), while the methods of using little data improve, the amounts of data available for Baltic Finnic languages is insufficient for large language modelling. Another aspect that one has to keep in mind is the quality of the data: for machine learning to work, the data needs to be representative: follow the standards that the chatbot-based AI is supposed to use and contain ample examples of correct usage in various genres. With limited data and plenty of non-standard usage, the large language models will not be usable for spell and grammar checking and correction, while rule-based approaches can be steered to prefer and suggest current norms if available.

Resources and evaluations

In this section we list grammatical models in the GiellaLT infrastructure as well as corpus resources in GiellaLT and elsewhere. The statistics shown in this chapter are valid for the time of writing, since the language models are developed constantly, the figures will be outdated by the time of publication already. For this reason, automated generation of resources and evaluations are evaluated in the continuous integration / continuous deployment (CI/CD) systems and presented as up-to-date online statistics (footnote: https://giellalt.github.io/CorpusResources.html). The relevant scripts are available in the github repositories (footnote: https://github.com/giellalt/giella-core and https://github.com/divvun/actions).

Grammatical models(¶ gm)

Within GiellaLT, there are grammatical models for 9 of the Finnic minority languages, cf. Table (see: models), which gives an overview of the lexical and morpho-syntactic descriptions of the language models in our infrastructure.. Only two of them are described in publications (Meänkieli (cites: trosterud2020sprakteknologi), Kven (cites: reino2017morphological)).

The size of morphosyntactic models can be measured in terms of how many lexemes they contain and the complexity of the morphophonological system can be approximated by combining the number of affixes used with the number of morphophonological alteration rules, covering suprasegmental and non-concatenative morphology as well as sandhi phenomena).

Table:[htb]

| Language | ISO | Stems | Affixes | Rules |

| —- | —- | —- | —- | —- |

| Ingrian | izh | 2,163 | 2,361 | 45 |

| Karelian | krl | 66,096 | 555 | 1 |

| Kven | fkv | 46,354 | 5,096 | 56 |

| Liv | liv | 15,276 | 6,247 | 68 |

| Livvi | olo | 60,008 | 5,456 | 84 |

| Ludic | lud | — | — | — |

| Meänkieli | fit | 65,872 | 3,436 | 63 |

| Veps | vep | 6,280 | 2,011 | 10 |

| Võro | vro | 36,591 | 8,672 | 156 |

| Votic | vot | 1,030 | 190 | 10 |

(Caption: Grammatical models in the GiellaLT infrastructure (https://giellalt.github.io/LanguageModels.html\#uralic)) (¶ models)

Corpora(¶ subsec:corpora)

We have also curated corpora for some of these languages. The corpora are used for the development of the language technology tools: we collect spelling and grammar errors to test and develop writers tools, we collect the words and word forms to test the morphological implementations and use the sentences to test the automatic machine translation, to name a few. The GiellaLT corpora are summarised in Table (see: tab:corpora).

There are also corpora for minority Finnic languages outside the Giellalt infrastructure. MetaShare contains a parallel corpus Võro - Estonian containing 171,252 Võro words as well as a monolingual Võro corpus of 350000 words (https://metashare.ut.ee). There are Bible texts available for Viena Karelian, Livvi and Veps (https://www.finugorbib.com), a parallel Bible corpus ((cites: pabivus-korp_fi)) and an open corpus containing (in total) 2,66 million words for the same languages (cf. (cites: boyko2022open) for a presentation).

Evaluation

Using the corpora, it is possible to measure a naïve coverage gives an impression of how much of real world texts can be successfully processed with the resulting analyser; a näive coverage is measured as a proportion of surface tokens that gets any analysis at all without considering correctness, this gives a rough estimate of how well the analyser models the language in the form that is used in real world texts. It may be noteworthy to remember that, in the case of minority languages, real world texts can show a variance of non-standard forms and orthographies wider than established and standardised majority languages. In order to perform more thorough evaluation, we would need to co-operate with a language expert and develop hand-annotated gold standard corpora, for this article, that is left for future work. To get a qualitative insight on the quality of the analysers (or the data), for example the commonest words that are not analysed for each languages are: (footnote: Both the source code for analysers and the corpora can be found at {https://github.com/giellalt), in the repositories lang-xxx and corpus-xxx, respectively, where xxx is the relevant ISO code. Compilation is docuented at {https://giellalt.github.io}. Analysis was run at Oct 18th 2025.}:

[noitemsep,parsep=0pt,partopsep=0pt] em Meänkieli: oova, och, nytten em Kven: kirj., muist, đ em Livvi: grigorianskoin, kargavusvuon, kalenduaruan em Veps: km, Vellest, nell em Võro: q, NOTOC, de

Table:

| Language | ISO | ktkn | MiB | Cov |

| —- | —- | —- | —- | —- |

| Meänkieli | fit | 528 | 12 | 90 % |

| Kven | fkv | 1,115 | 21 | 92 % |

| Livvi | olo | 242 | 4 | 87 % |

| Veps | vep | 859 | 9 | 88 % |

| Võro | vro | 265 | 4 | 90 % |

| Finnish | fin | 16,694 | 382 | — |

(Caption: Corpora in the GiellaLT infrastructure. Finnish is listed for its relevance to machine translation. ktkn = thousand tokens, MiB = million bytes, Cov = coverage, or percentage re cognised by the analyser.) (¶ tab:corpora)

Practical tools

Several language technology tools and softwares are implemented based on the morphological analysers and text collection. These tools are developed to support the language community, language revitalisation, standardisation, etc. We provide here experimental results of using these analysers in the context of these applications and corpora.

Keyboards and proofing tools

Keyboard drivers and tools for checking written language and correcting mistakes

are crucial for literacy development in the digital era. Each literary language

needs its own keyboard layout, for several reasons. The Finnic languages have

different sets of letters in addition to the basic a-z set, typically around 6

additional ones, but ranging from 3 (Meänkieli) to 21 (Livonian). The optimal

keyboard should be a compromise between keyboard tradition and placement of

letters according to their frequency in running text. Then the keyboard users

will expect non-letter symbols to be in the same positions as they are on the

majority language keyboard. Kven and Meänkieli share the same alphabet (except

for the Kven đ), but in addition, symbols such as @, ’, §, \$,

€ are placed (and engraved!) on different positions on Norwegian and Swedish

keyboards, and the users of each minority language will expect these symbols to

be in the same positions as they hold on the majority language keyboard.

Finally, in Windows, the language of third-party proofing tools are identified

by sharing ISO code with a keyboard driver. The same goes for mobile phones,

where language support is always linked to the keyboard language.

The GiellaLT infrastructure contains a pipeline for easily setting up keyboard layouts for all computer and mobile phone operative systems, as well as keyboards for 8 of the Finnic minority languages (footnote: For an overview and links to the keyboards, see https://giellalt.github.io/KeyboardLayouts.html#uralic-languages).

Proofing tools include spell-checking and correction as well as grammatical error correction. The GiellaLT infrastructure is set up so that even a grammatical model can be turned into a spellchecker. The availability of proofing tools is thus obviously dependent upon the quality of the language model. The language models (see Table (see: models)) are classified according to a 4-grade evaluation scale (footnote: For a definition of the various grades, see https://giellalt.github.io/MaturityClassification.html). In addition, the spellchecker is dependent upon a suggestion mechanism as well as a text corpus in order to give precedence to more common words when correcting. A minimal suggestion mechanism contains approximately 50 rules (one for each letter or symbol to be suggested). Even a well-developed spellchecker in the GiellaLT does not contain more than appr. 300 suggestion rules. Table (see: tools) gives an overview of status for the Finnic minority languages.

Table:[htb]

| Language | ISO | Keyb | Spell | Sugg | W |

| —- | —- | —- | —- | —- | —- |

| Ingrian | izh | yes | Beta | 56 | — |

| Karelian | krl | yes | Alpha | 89 | — |

| Kven | fkv | yes | Prod. | 301 | yes |

| Liv | liv | yes | Alpha | 109 | — |

| Livvi | olo | yes | Beta | 88 | — |

| Ludic | lud | — | — | — | — |

| Meänkieli | fit | yes | Beta | 220 | yes |

| Veps | vep | — | Alpha | 68 | — |

| Võro | vro | yes | Beta | 62 | — |

| Votic | vot | yes | — | — | — |

(Caption: Proofing tools in the GiellaLT infrastructure. Spell = quality level, Sugg = number of suggestion rules, W = corpus for weighting of suggestions) (¶ tools)

Rule-based machine translation

There are 6 Finnic language pairs within the Apertium (cites: khanna2021recent) rule-based machine translation system, cf. Table (see: tab:mt). Each language pair contains bilingual dictionaries, grammatical language models for analysis of L1 and generation of L2 as well as grammars for lexical selection and grammatical differences. As can be seen from the number of lexical entries, the language pairs range from usable machine translators to early stage projects.

Table:[]

| Pair | Entries |

| —- | —- |

| Finnish—Livvi | 30,212 |

| Karelian—Livvi | 6,419 |

| Finnish—Kven | 4,624 |

| Karelian—Finnish | 2,297 |

| Vorõ—Estonian | 161 |

| Livonian—Finnish | 37 |

(Caption: Machine translation models(¶ tab:mt))

Neural machine translation(¶ neural)

The neural machine translation project Neurotõlge (neurotolge.ee, see (cites: yankovskaya2023machine)) offers machine translation between (among other Uralic languages) the Finnic minority languages Livvi Karelian, Viena Karelian, Lude, Veps, Livonian and Võro and the majority languages Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian Bokmål and Russian. The monolingual corpora presented in (cites: yankovskaya2023machine[765]) range from 5,000 (Ludic) to 115,300 and 162,000 (Veps and Võro) sentences. The amount of parallel sentences for the languages in Russia with Russian are 10,000 – 27,000, with the Bible dominating for all languages except Ludic.

Compared to their result for Finnish to Inari Saami and Norwegian to South Saami (which boast the quite good BLEU scores of 67.34 and 60.79, respectively), their results for the Finnic languages (op.cit. p. 768) are far worse (BLEU 24.17 for Estonian to Livonian and 30.63 for Estonian to Võro, the latter even worse than their previous result of 34.11). As shown by (cites: yankovskaya2023machine), the main reason for this is the paucity of text, and the lack of balance for the parallel text, for the Finnic languages.

There are some existing critical evaluations of Neurotõlge for Sámi languages, c.f. (cites: wiechetek-etal-2024-ethical,wiechetek2023manual), but these evaluations concentrate upon key semantic and grammatical elements of the translated texts rather than the overall closeness between translation and reference, as (cites: yankovskaya2023machine) do.

Possibilities and perspectives

There are grammatical models for most Finnic minority languages, they show a coverage for running text on around or slightly 90 % (cf. Table (see: tab:corpora)). This is typical result achieved by rewriting formal grammars as grammar models. Grammars are seldom comprehensive, they typically sketch main patterns and obvious exceptions. In order to go the time-consuming work of getting a coverage of, say, 98 %, one has to include native speakers with knowledge of the norm in the team, so that they can add the description not included in the grammars. It is thus important that language researchers, teachers and learners are included in the process.

One way that the teachers and learners might help, is to simply provide paradigmatic information on word inflection. Providing simple information on a single word häkki+N+Sg+Ade: häkil, for example, provides the coder with information on gradation, and an adjacent plural form häkki+N+Pl+Ade: häkkilöil. These bits of information can be generated in a class environment where each student is given nouns, verbs or adjectives to describe in paradigms. The teacher checks to see that the forms are correct and the paradigmatic information is added to the infrastructure testing.

The GiellaLT infrastructure provides two different kinds of testing: One is impressionistic testing: Tools that generate parts of the model for the developer to inspect (e.g. generating all forms of a certain case). Another type is regression testing. Here, the linguist has set up for example model paradigms for parts of the morphology, and the model is tested continuously in order to ensure that it does not get worse.

There are test paradigms for the grammatical models of the Finnich minority languages to a various degree. Table (see: paradigm) gives an overview of paradigm cells in the testing setup for the different languages. The figures might provide us with a picture of the time allocated to developing the different models. One could, of course, also add language-form information to the paradigmatic information, which could help solve problems in Veps, for example, where the Veps magazine Kodima (footnote: https://omamedia.ru/fi/publication/kodima) and the Veps edition of Wikipedia (footnote: https://vep.wikipedia.org) are written in two different orthographies.

Table:[]

| Language | Paradigm info |

| —- | —- |

| Kven | 10,557 |

| Livonian | 5,693 |

| Livvi | 3,538 |

| Meänkieli | 1,526 |

| Veps | 392 |

| Võro | 4,023 |

(Caption: Paradigm info(¶ paradigm))

There is always a continuum of dialects and languages and standards within these minority languages, one benefit of rule-based approaches is that they offer good control over the variation: It is possible to implement morphophonological rules and lexical analyses that concern specific variants. When this language technology is combined with a tool like spell-checking and correction, it is a powerful tool for language normativisation and support of writing culture. Experience with Kven has shown that the same lexica and morphological tagging structures can be used for describing language variants by river valley. Applied to Karelian languages, this might allow us to share mutual word stems, on the one hand, but distinguish morphological branches on the other. When it comes to sharing mutual lexica, it should be noted that the shared lexica are set off as their own groups. In work with Saami languages, proper noun lexica are shared. Even here, however, not all proper nouns can be shared. In work with the Permyak-Komi and Zyrian-Komi, additional sharing of lexica has been included for 100% matches in Russian loan words. For the Karelian languages using shared lexica is dependent on the use of parallel phonematic writing practices.

For future work, there is a lot that can be done in curating more lexical data and corpora for these languages. There is also a potential of developing speech technology applications based on the example of existing systems in Sámi languages. All of this requires collaboration, of course, between language communities and computational linguists. An important and ever more relevant issue in collaboration of language communities and computational linguists is ethical issues related to ownership of the language data and language itself, there has been a lot of research on this topic by us and others and we want to point towards (cites: wiechetek-etal-2024-ethical,wiechetek2022unmasking) for further references.

Conclusion

In this article, we have summarised the state of the art in minority Finnic language technology. We have shown that there exist some resources and have compared them to related languages to highlight the potential future possibilities these languages already have available.

The main part of the language technology work on Finnic so far has been concentrated on language models and proofing tools. For 5 of the 9 languages, we have developed grammatical models showing a coverage on running text extending 85 % (for three of them, 90 %).

The situation for available corpora is rather limited. Only for Kven and Meänkieli are there text collections available other than text from (Incubator) Wikipedias. To what extent the content of the corpora follow established standards is unclear. The corpora referred to here do not include all published text, but it is clear that the basis for data-driven language technology is shaky. In this perspective, we note on the positive side that despite this, there is neural-based MT for 5 of the languages presented here.

References

- koskenniemi2012finnish:

- title: The Finnish Language in the Digital Age

- author: Koskenniemi, Kimmo and Krister Lindén and Lauri Carlsson and…

- editor: Rehm, Georg and Uszkoreit, Hans

- year: 2012

- url: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-642-27248-6

- publisher: Springer

- liin2012estonian:

- title: The Estonian Language in the Digital Age

- author: Krista Liin andKadri Muischnek andKaili Müürisep and

- editor: Rehm, Georg and Uszkoreit, Hans

- year: 2012

- publisher: Springer

- simon2012hungarian:

- title: The Hungarian Language in the Digital Age

- author: Simon, Eszter andLendvai, Piroska andNémeth, Géza andOlaszy,…

- editor: Rehm, Georg and Uszkoreit, Hans

- year: 2012

- publisher: Springer

- muischnek2022report:

- author: Kadri Muischnek

- title: Report on the Estonian Language

- volume: D1.12

- publisher: European Language Equality (ELE)} ,

- year: 2022,

- address: Berlin

- linden2022report:

- author: Krister Linden and Wilhelmina Dyster

- title: Report on the Finnish Language

- series: D1.13

- publisher: European Language Equality (ELE)} ,

- year: 2022,

- address: Berlin

- jelencsik-matyus2022report:

- author: Kinga Jelencsik-Mátyus and Enikő Héja and Zsófia Varga and T…

- title: Report on the Hungarian Language

- series: D1.13

- publisher: European Language Equality (ELE)} ,

- year: 2022,

- address: Berlin

- moshagen2022report:

- author: Sjur Nørstebø Moshagen and Rickard Domeij and Kristine Eide …

- title: Report on the Nordic Minority Languages

- series: D1.38

- publisher: European Language Equality (ELE)

- year: 2022,

- address: Berlin

- steingrimsson2024language:

- author: Steinþór Steingrímsson and Iben Nyholm Debess and Kimmo

- title: Language Technology for Less-Resourced Languages in the

- publisher: Stjórnaráð Íslands

- year: 2024,

- address: Reykjavik

- pirinen-etal-2023-giellalt:

- title: GiellaLT {—} a stable infrastructure for Nordic minority

- author: Pirinen, Flammie and

- booktitle: Proceedings of the 24th Nordic Conference on Computational

- month: may,

- year: 2023

- address: Tórshavn, Faroe Islands

- publisher: University of Tartu Library

- url: https://aclanthology.org/2023.nodalida-1.63

- pages: 643–649

- moshagen2023giellalt:

- author: Sjur Nørstebø Moshagen and Flammie Pirinen and Lene

- date-added: 2023-04-18 09:24:27 +0200

- date-modified: 2023-04-18 09:27:51 +0200

- keywords: rule-based language technology, giellalt, Infrastructure

- pages: 70-94

- series: NEALT Monograph Series

- title: The GiellaLT infrastructure: A multilingual infrastructure

- volume: 2

- year: 2023

- publisher: NEALT

- khanna2021recent:

- author: Khanna, Tanmai and Washington, Jonathan North and Tyers, Fra…

- doi: 10.1007/s10590-021-09260-6

- journal: Machine Translation

- month: 10

- publisher: Springer

- title: Recent advances in Apertium, a free/open-source rule-based

- year: 2021

- yankovskaya2023machine:

- title: Machine Translation for Low-resource Finno-Ugric Languages

- author: Yankovskaya, Lisa andTars, Maali and

- booktitle: Proceedings of the 24th Nordic Conference on Computational L…

- month: may,

- year: 2023

- address: Tórshavn, Faroe Islands

- publisher: University of Tartu Library

- url: https://aclanthology.org/2023.nodalida-1.77

- pages: 762–771

- rantanen2022best:

- author: Rantanen, T. and Tolvanen, H. and Roose, M. and Ylikoski, J.

- title: Best practices for spatial language data harmonization, shar…

- journal: PLoS ONE

- year: 2022,

- volume: 17,

- number: 6,

- url: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269648

- Viitso-et-al-2012-livokiel:

- author: Tiit-Rein Viitso and Valts Ernštreits

- title: Līvõkīel-ēstikīel-leţkīel sõnārōntõz:

- publisher: Tartu Ülikool, and Latviešu valodas aģentūra

- year: 2012

- laakso2022livonian:

- title: Livonian

- author: Johanna Laakso

- year: 2022,

- booktitle: The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages

- publisher: Oxford

- pages: 380-391

- editor: Bakró-Nagy, Marianne and Laakso, Johanna and Skribni

- grunthal2022veps:

- title: Veps

- author: Riho Grünthal

- year: 2022,

- booktitle: The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages

- publisher: Oxford

- pages: 291-307

- editor: Bakró-Nagy, Marianne and Laakso, Johanna and Skribnik, Elena

- bakro-nagy2022uralic:

- series: Oxford Guides to the World’s Languages

- publisher: Oxford University Press, Incorporated

- isbn: 0198767668

- year: 2022

- title: The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages

- edition: 1

- language: eng

- address: Oxford

- editor: Bakró-Nagy, Marianne and Laakso, Johanna and Skribnik, Elena

- keywords: Uralic languages

- markus2022ingrian:

- author: Markus, Elena and Rozhanskiy, Fedor

- isbn: 9780198767664

- title: Ingrian

- booktitle: The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages

- publisher: Oxford University Press

- year: 2022

- month: 03

- doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0018

- url: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0018

- eprint: https://academic.oup.com/book/0/chapter/366304258/chapter-pd…

- sarhimaa2022karelian:

- author: Sarhimaa, Anneli

- isbn: 9780198767664

- title: Karelian

- booktitle: The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages

- publisher: Oxford University Press

- year: 2022

- month: 03

- doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0016

- url: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0016

- eprint: https://academic.oup.com/book/0/chapter/366303647/chapter-pd…

- pajusalo2022seto:

- author: Pajusalu, Karl

- isbn: 9780198767664

- title: Seto South Estonian

- booktitle: The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages

- publisher: Oxford University Press

- year: 2022

- month: 03

- doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0021

- url: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0021

- eprint: https://academic.oup.com/book/0/chapter/366305634/chapter-pd…

- markus2022votic:

- author: Markus, Elena and Rozhanskiy, Fedor

- isbn: 9780198767664

- title: Votic

- booktitle: The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages

- publisher: Oxford University Press

- year: 2022

- month: 03

- doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0019

- url: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0019

- eprint: https://academic.oup.com/book/0/chapter/366304754/chapter-pd…

- abondolo2023uralic:

- title: The Uralic Languages

- editor: Daniel Abondolo and Riitta-Liisa Valijärvi

- publisher: Routledge

- year: 2023

- grunthal2023finnic:

- author: Riho Grünthal

- booktitle: The Uralic Languages

- publisher: Routledge

- year: 2023,

- title: The Finnic languages

- pladoetal2022voro:

- author: Helen Plado and Liina Lindström and Sulev Iva

- booktitle: The Uralic Languages

- publisher: Routledge

- year: 2023,

- title: Võro South Estonian

- soderholm2017kvensk:

- author: Eira Söderholm

- title: Kvensk grammatikk

- publisher: Cappelen Damm

- address: Oslo

- year: 2017,

- url: https://cdforskning.no/cdf/catalog/book/24

- pohjanen2022meankieli:

- author: Bengt Pohjanen

- title: Meänkieli – Grammatik, lärobok, historik, texter

- publisher: Barents Publisher

- address: Överkalix

- url: https://www.isof.se/nationella-minoritetssprak/meankieli/for…

- year: 2022

- beesley2003finite:

- author: Kenneth R Beesley and Lauri Karttunen

- flammie: fsa

- isbn: 978-1575864341

- pages: 503

- publisher: CSLI publications

- title: Finite State Morphology

- year: 2003

- karlsson1990constraint:

- address: Helsinki

- author: Fred Karlsson

- booktitle: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference of

- editor: H. Karlgren

- pages: 168–173

- title: Constraint Grammar as a Framework for Parsing Unrestricted T…

- volume: 3

- year: 1990

- koskenniemi1983twolevel:

- author: Kimmo Koskenniemi

- school: University of Helsinki

- title: Two-level Morphology: A General Computational Model for Word…

- url: http://www.ling.helsinki.fi/koskenni/doc/Two-LevelMorphology…

- year: 1983

- linden2009hfst:

- Author: Krister Lindén and Miikka Silfverberg and Flammie A Pirinen

- Booktitle: sfcm 2009

- Crossref: sfcm2009

- Pages: 28—47

- Title: HFST Tools for Morphology—An Efficient Open-Source Package…

- Year: 2009

- bick2015cg:

- author: Eckhard Bick and Tino Didriksen

- booktitle: Proceedings of the 20th Nordic Conference of Computational

- issn: 1650-3740

- pages: 31-39

- publisher: Linköping University Electronic Press, Linköpings

- title: CG-3 – Beyond Classical Constraint Grammar

- year: 2015

- rueter2024testing:

- author: Jack Rueter

- title: Testing and enhancement of language models (transducers) fro…

- journal: HAL

- id: hal-04828974

- url: https://hal.science/hal-04828974v1

- year: 2024

- month: dec

- note: 23 pages

- ud214:

- title: Universal Dependencies 2.14

- author: Zeman, Daniel and Nivre, Joakim and Abrams, Mitchell and Ack…

- url: http://hdl.handle.net/11234/1-5502

- note: LINDAT/{CLARIAH}-CZ digital library at the Institute of Form…

- copyright: Licence Universal Dependencies v2.14

- year: 2024

- pirinen2019building:

- author: Pirinen, Flammie A

- booktitle: Proceedings of the Universal Dependencies Workshop 2019

- misc: (to appear)

- title: Building minority dependency treebanks, dictionaries andcomp…

- year: 2019

- raisanen2024kvensk:

- title: Kvensk revitalisering, normering og leksikografi

- volume: 1

- url: https://tidsskrift.dk/lexn/article/view/151290

- DOI: 10.7146/ln.v1i31.151290

- number: 31

- journal: LexicoNordica

- author: Räisänen, Anna-Kaisa and Eriksen, Aili and Brevik Kjærstad, …

- year: 2024

- month: dec.

- hiovain2023developing:

- title: Developing TTS and ASR for Lule and North Sámi languages

- author: Hiovain-Asikainen, Katri and De la Rosa, Javier

- booktitle: Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Meeting of the ELRA/ISCA SIG o…

- pages: 48–52

- year: 2023

- laakso2022graphization:

- title: Graphization and orthographies of Uralic minority languages

- author: Johanna Laakso and Elena Skribnik

- year: 2022,

- booktitle: The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages

- publisher: Oxford

- pages: 91–100

- editor: Bakró-Nagy, Marianne and Laakso, Johanna and Skribnik, Elena

- boyko2022open:

- title: The Open Corpus of the Veps and Karelian Languages: Overview…

- ISSN: 2518-668X

- url: http://dx.doi.org/10.18502/kss.v7i3.10419

- DOI: 10.18502/kss.v7i3.10419

- journal: KnE Social Sciences

- publisher: Knowledge E DMCC

- author: Boyko, Tatyana and Zaitseva, Nina and Krizhanovskaya, Natali…

- year: 2022

- month: feb

- trosterud2020sprakteknologi:

- author: Trond Trosterud

- title: Språkteknologi för meänkieli

- year: 2020,

- address: UiT The Arctic University of Norâay

- URL: https://giellalt.github.io/lang-fit/rapport.pdf

- reino2017morphological:

- author: Sindre Reino Trosterud and Trond Trosterud and Anna-Kaisa

- date-modified: 2020-01-04 15:48:14 +0200

- doi: 10.18653/v1/W17-0608

- keywords: FST, Kven

- location: St. Petersburg, Russia

- pages: 76–88

- publisher: Association for Computational Linguistics

- title: A morphological analyser for Kven

- url: http://aclanthology.coli.uni-saarland.de/pdf/W/W17/W17-0608….

- year: 2017

- bdsk-url-1: http://aclanthology.coli.uni-saarland.de/pdf/W/W17/W17-0608….

- bdsk-url-2: https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/W17-0608}

- pabivus-korp_fi:

- author: {Helsingin yliopisto, FIN-CLARIN} and Jack Rueter and Erik A…

- year: 2022

- title: {Raamatun jakeita uralilaisille kielille, rinnakkaiskorpus, …

- publisher: Kielipankki

- type: aineisto

- url: http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:lb-2020021121

- wiechetek-etal-2024-ethical:

- title: The Ethical Question {–} Use of Indigenous Corpora for Larg…

- author: Wiechetek, Linda and

- editor: Calzolari, Nicoletta and

- booktitle: Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on

- month: may,

- year: 2024

- address: Torino, Italia

- publisher: ELRA and ICCL

- url: https://aclanthology.org/2024.lrec-main.1383/

- pages: 15922–15931

- wiechetek2023manual:

- title: A Manual Evaluation Method of Neural MT for Indigenous Langu…

- author: Wiechetek, Linda and Pirinen, Flammie and Kummervold, Per

- booktitle: Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Human Evaluation of NLP S…

- pages: 1–10

- year: 2023

- wiechetek2022unmasking:

- address: Marseille, France

- author: Wiechetek, Linda and Hiovain-Asikainen, Katri and Mikkel…

- booktitle: Proceedings of the Language Resources and Evaluation

- month: June

- pages: 1167–1177

- publisher: European Language Resources Association

- title: Unmasking the Myth of Effortless Big Data - Making an Open S…

- url: https://aclanthology.org/2022.lrec-1.125

- year: 2022

Converted with Flammie’s latex2markdown v.0.1.0